Cambridge IELTS 11 Reading Test 02 Vocabulary List

Page Contents

READING PASSAGE 1

Raising the Mary Rose

How a sixteenth-century warship was recovered from the seabed

On 19 July 1545, English and French fleets were engaged in a sea battle off the coast of southern England in the area of water called the Solent, between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight. Among the English vessels was a warship by the name of Mary Rose. Built in Portsmouth some 35 years earlier, she had had a long and successful fighting career, and was a favourite of King Henry VIII. Accounts of what happened to the ship vary: while witnesses agree that she was not hit by the French, some maintain that she was outdated, overladen and sailing too low in the water, others that she was mishandled by undisciplined crew. What is undisputed, however, is that the Mary Rose sank into the Solent that day, taking at least 500 men with her. After the battle, attempts were made to recover the ship, but these failed.

The Mary Rose came to rest on the seabed, lying on her starboard (right) side at an angle of approximately 60 degrees. The hull (the body of the ship) acted as a trap for the sand and mud carried by Solent currents. As a result, the starboard side filled rapidly, leaving the exposed port (left) side to be eroded by marine organisms and mechanical degradation. Because of the way the ship sank, nearly all of the starboard half survived intact. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the entire site became covered with a layer of hard grey clay, which minimised further erosion.

Then, on 16 June 1836, some fishermen in the Solent found that their equipment was caught on an underwater obstruction, which turned out to be the Mary Rose. Diver John Deane happened to be exploring another sunken ship nearby, and the fishermen approached him, asking him to free their gear. Deane dived down, and found the equipment caught on a timber protruding slightly from the seabed. Exploring further, he uncovered several other timbers and a bronze gun. Deane continued diving on the site intermittently until 1840, recovering several more guns, two bows, various timbers, part of a pump and various other small finds.

The Mary Rose then faded into obscurity for another hundred years. But in 1965, military historian and amateur diver Alexander McKee, in conjunction with the British Sub-Aqua Club, initiated a project called ‘Solent Ships’. While on paper this was a plan to examine a number of known wrecks in the Solent, what McKee really hoped for was to find the Mary Rose. Ordinary search techniques proved unsatisfactory, so McKee entered into collaboration with Harold E. Edgerton, professor of electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 1967, Edgerton’s side-scan sonar systems revealed a large, unusually shaped object, which McKee believed was the Mary Rose.

Further excavations revealed stray pieces of timber and an iron gun. But the climax to the operation came when, on 5 May 1971, part of the ship’s frame was uncovered. McKee and his team now knew for certain that they had found the wreck, but were as yet unaware that it also housed a treasure trove of beautifully preserved artefacts. Interest ^ in the project grew, and in 1979, The Mary Rose Trust was formed, with Prince Charles as its President and Dr Margaret Rule its Archaeological Director. The decision whether or not to salvage the wreck was not an easy one, although an excavation in 1978 had shown that it might be possible to raise the hull. While the original aim was to raise the hull if at all feasible, the operation was not given the go-ahead until January 1982, when all the necessary information was available.

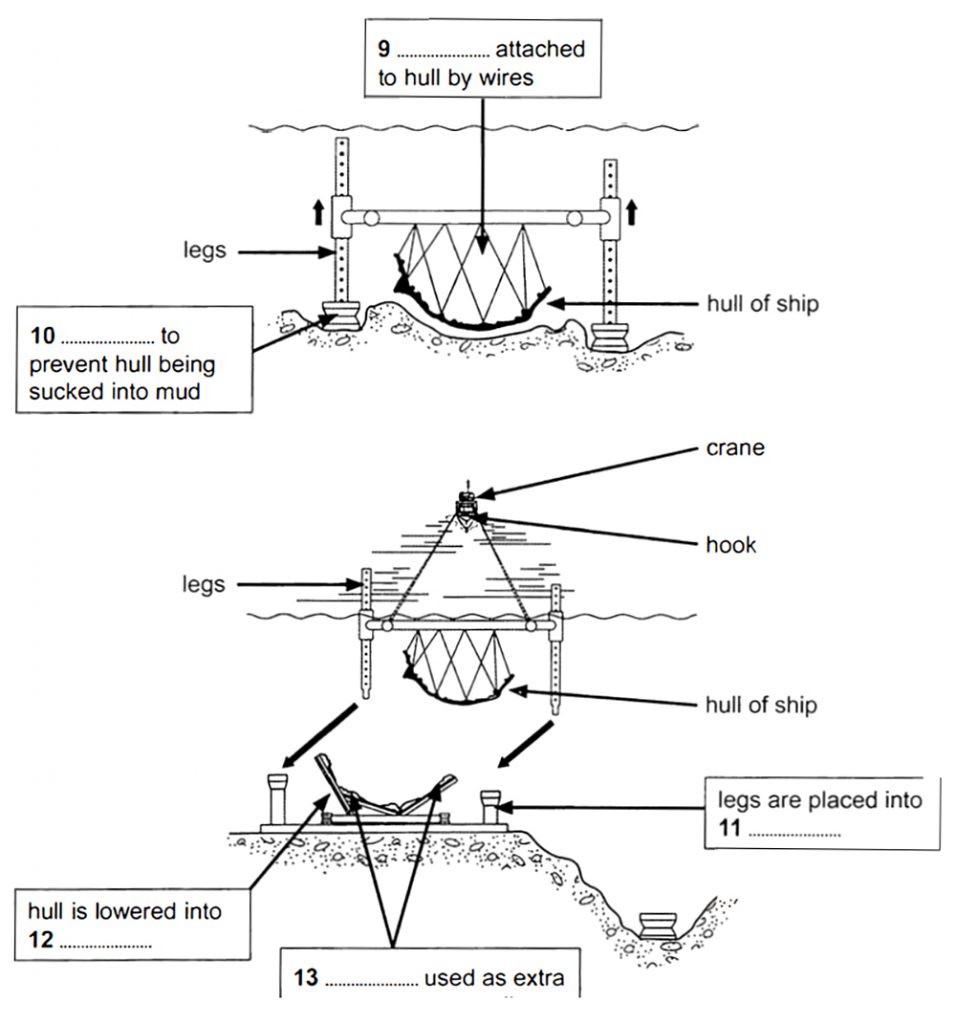

An important factor in trying to salvage the Mary Rose was that the remaining hull was an open shell. This led to an important decision being taken: namely to carry out the lifting operation in three very distinct stages. The hull was attached to a lifting frame via a network of bolts and lifting wires. The problem of the hull being sucked back downwards into the mud was overcome by using 12 hydraulic jacks. These raised it a few centimetres over a period of several days, as the lifting frame rose slowly up its four legs. It was only when the hull was hanging freely from the lifting frame, clear of the seabed and the suction effect of the surrounding mud, that the salvage operation progressed to the second stage. In this stage, the lifting frame was fixed to a hook attached to a crane, and the hull was lifted completely clear of the seabed and transferred underwater into the lifting cradle. This required precise positioning to locate the legs into the stabbing guides’ of the lifting cradle. The lifting cradle was designed to fit the hull using archaeological survey drawings, and was fitted with air bags to provide additional cushioning for the hull’s delicate timber framework. The third and final stage was to lift the entire structure into the air, by which time the hull was also supported from below. Finally, on 11 October 1982, millions of people around the world held their breath as the timber skeleton of the Mary Rose was lifted clear of the water, ready to be returned home to Portsmouth.

Raising the hull of the Mary Rose: Stages one and two

Cambridge IELTS 11 Reading Test 02

Vocabulary List for READING PASSAGE 1

- warship —a ship equipped with weapons and designed to take part in warfare at sea.

- seabed -noun- the ground under the sea; the ocean floor.

- fleets – plural noun: fleets-a group of ships sailing together, engaged in the same activity, or under the same ownership.“the small port supports a fishing fleet”

- overladen –adjective- having too large or too heavy a load. “an overladen trolley”

- mishandled verb – past tense: mishandled; past participle: mishandled. 1.manage or deal with (something) wrongly or ineffectively. “the officer had mishandled the situation”

- undisputed – adjective – not disputed or called in question; accepted. “the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world”

- starboard – noun – the side of a ship or aircraft that is on the right when one is facing forward. “I made a steep turn to starboard”

- eroded – gradually destroy or be gradually destroyed. “this humiliation has eroded what confidence Jean has”

- marine organisms – Marine organism means any animal, plant or other life that inhabits waters below head of tide.

- mechanical degradation – Mechanical degradation describes the breakdown of molecules in the high flow rate region close to a well as a result of high mechanical stresses on the macromolecules. This short-term effect is important only in the reservoir near the wellbore (and also in some of the polymer handling equipment, in chokes, and so on).

- underwater obstruction – A natural or artificial obstacle which is located to seaward of the high-water line and wholly or partly submerged, and which acts as a barrier or obstruction to the passage of ships, landing ships, craft, vehicles, or torpedoes.

- timber noun 1. wood prepared for use in building and carpentry. “the exploitation of forests for timber”

- protruding – to stick out or cause to stick out. Protrude means to stick out. A gravestone protrudes from the ground, a shelf protrudes from a wall, a lollipop stick protrudes from your mouth. From the Latin prō- “forward, out” + trūdere “to thrust,” protrude often describes coastlines where rocks stick out into the water.

- intermittently -adverb-at irregular intervals; not continuously or steadily. “he has worked intermittently in a variety of jobs”

- The bow and arrow – is a ranged weapon system consisting of an elastic launching device and long-shafted projectiles. Humans used bows and arrows for hunting and aggression long before recorded history, and the practice was common to many prehistoric cultures

- faded – past tense: faded; past participle: faded 1. gradually grow faint and disappear. “the light had faded and dusk was advancing” The smile faded from his face.

- obscurity – the state of being not clear and difficult to understand or see: The story is convoluted and opaque, often to the point of total obscurity.

- amateur diver– engaging or engaged in without payment; non-professional. “amateur athletics”

- Conjunction – the action or an instance of two or more events or things occurring at the same point in time or space. “a conjunction of favourable political and economic circumstances”

- wrecks – plural noun: wrecks 1. the destruction of a ship at sea; a shipwreck. “the survivors of the wreck”

- climax– noun-the most intense, exciting, or important point of something; the culmination. “she was nearing the climax of her speech”

- unaware – adjective –having no knowledge of a situation or fact. – “they were unaware of his absence”

- trove -noun –a store of valuable or delightful things. “the cellar contained a trove of rare wines”

- artefacts – plural noun: artefacts –1. an object made by a human being, typically one of cultural or historical interest. “gold and silver artefacts”

- salvage – to save goods from damage or destruction, especially from a ship that has sunk or been damaged or a building that has been damaged by fire or a flood: gold coins salvaged from a shipwreck

- hydraulic jacks -A hydraulic jack is a device that is used to lift heavy loads by applying a force via a hydraulic cylinder. Hydraulic jacks lift loads using the force created by the pressure in the cylinder chamber.

- suction effect -Suction/injection is a mechanical effect and used to control the energy losses in the boundary layer region by reducing the drag on the surface.

- cushioning – The meaning of CUSHIONING is protection against force or shock provided by a cushion.

- delicate -easily broken or damaged; physically weak; fragile; frail: delicate porcelain;a delicate child. so fine as to be scarcely perceptible; subtle: a delicate flavor.

- muggers-plural noun: muggers- a person who attacks and robs another in a public place. “the mugger snatched my purse and ran away”

- Cambridge IELTS 11 Reading Test 02

Cambridge IELTS 11 Reading Test 02

READING PASSAGE 2

What destroyed the civilisation of Easter Island?

A

Easter Island, or Rapu Nui as it is known locally, is home to several hundred ancient human statues – the moai. After this remote Pacific island was settled by the Polynesians, it remained isolated for centuries. All the energy and resources that went into the moai – some of which are ten metres tall and weigh over 7,000 kilos – came from the island itself. Yet when Dutch explorers landed in 1722, they met a Stone Age culture. The moai were carved with stone tools, then transported for many kilometres, without the use of animals or wheels, to massive stone platforms. The identity of the moai builders was in doubt until well into the twentieth century. Thor Heyerdahl, the Norwegian ethnographer and adventurer, thought the statues had been created by pre-Inca peoples from Peru. Bestselling Swiss author Erich von Daniken believed they were built by stranded extraterrestrials. Modern science – linguistic, archaeological and genetic evidence – has definitively proved the moai builders were Polynesians, but not how they moved their creations. Local folklore maintains that the statues walked, while researchers have tended to assume the ancestors dragged the statues somehow, using ropes and logs.

B

When the Europeans arrived, Rapa Nui was grassland, with only a few scrawny trees. In the 1970s and 1980s, though, researchers found pollen preserved in lake sediments, which proved the island had been covered in lush palm forests for thousands of years. Only after the Polynesians arrived did those forests disappear. US scientist Jared Diamond believes that the Rapanui people – descendants of Polynesian settlers – wrecked their own environment. They had unfortunately settled on an extremely fragile island – dry, cool, and too remote to be properly fertilised by windblown volcanic ash. When the islanders cleared the forests for firewood and farming, the forests didn’t grow back. As trees became scarce and they could no longer construct wooden canoes for fishing, they ate birds. Soil erosion decreased their crop yields. Before Europeans arrived, the Rapanui had descended into civil war and cannibalism, he maintains. The collapse of their isolated civilisation, Diamond writes, is a ’worst-case scenario for what may lie ahead of us in our own future’.

C

The moai, he thinks, accelerated the self-destruction. Diamond interprets them as power displays by rival chieftains who, trapped on a remote little island, lacked other ways of asserting their dominance. They competed by building ever bigger figures. Diamond thinks they laid the moai on wooden sledges, hauled over log rails, but that required both a lot of wood and a lot of people. To feed the people, even more land had to be cleared. When the wood was gone and civil war began, the islanders began toppling the moai. By the nineteenth century none were standing.

D

Archaeologists Terry Hunt of the University of Hawaii and Carl Lipo of California State University agree that Easter Island lost its lush forests and that it was an ‘ecological catastrophe’ – but they believe the islanders themselves weren’t to blame. And the moai certainly weren’t. Archaeological excavations indicate that the Rapanui went to heroic efforts to protect the resources of their wind-lashed, infertile fields. They built thousands of circular stone windbreaks and gardened inside them, and used broken volcanic rocks to keep the soil moist. In short, Hunt and Lipo argue, the prehistoric Rapanui were pioneers of sustainable farming.

E

Hunt and Lipo contend that moai-building was an activity that helped keep the peace between islanders. They also believe that moving the moai required few people and no wood, because they were walked upright. On that issue, Hunt and Lipo say, archaeological evidence backs up Rapanui folklore. Recent experiments indicate that as few as 18 people could, with three strong ropes and a bit of practice, easily manoeuvre a 1,000 kg moai replica a few hundred metres. The figures’ fat bellies tilted them forward, and a D-shaped base allowed handlers to roll and rock them side to side.

F

Moreover, Hunt and Lipo are convinced that the settlers were not wholly responsible for the loss of the island’s trees. Archaeological finds of nuts from the extinct Easter Island palm show tiny grooves, made by the teeth of Polynesian rats. The rats arrived along with the settlers, and in just a few years, Hunt and Lipo calculate, they would have overrun the island. They would have prevented the reseeding of the slow-growing palm trees and thereby doomed Rapa Nui’s forest, even without the settlers’ campaign of deforestation. No doubt the rats ate birds’ eggs too. Hunt and Lipo also see no evidence that Rapanui civilisation collapsed when the palm forest did. They think its population grew rapidly and then remained more or less stable until the arrival of the Europeans, who introduced deadly diseases to which islanders had no immunity. Then in the nineteenth century slave traders decimated the population, which shrivelled to 111 people by 1877.

G

Hunt and Lipo’s vision, therefore, is one of an island populated by peaceful and ingenious moai builders and careful stewards of the land, rather than by reckless destroyers ruining their own environment and society. ‘Rather than a case of abject failure, Rapu Nui is an unlikely story of success’, they claim. Whichever is the case, there are surely some valuable lessons which the world at large can learn from the story of Rapa Nui.

Cambridge IELTS 11 Reading Test 02

Vocabulary List for READING PASSAGE 2

- statues – stat·ue ˈsta-(ˌ)chü : a three-dimensional representation usually of a person, animal, or mythical being that is produced by sculpturing, modeling, or casting.

- Stone Age culture – The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make stone tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years, and ended between 4,000 BC and 2,000 BC, with the advent of metalworking.

- carved 1 : to cut with care or precision – carved fretwork 2 : to make or get by or as if by cutting —often used with out carve out a career

- ethnographer – Ethnography is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject of the study. –ethnographer a person who studies and describes the culture of a particular society or group: She became an accomplished linguist and ethnographer.

- pre-Inca – pre-Incan – noun: a native of Bolivia, Ecuador, or Peru of the prehistoric period preceding the rise of the Inca Empire

- extraterrestrial – adjective -of or from outside the earth or its atmosphere. “searches for extraterrestrial intelligence” – noun – a hypothetical or fictional being from outer space.

- logs – noun – plural noun: logs – 1. a part of the trunk or a large branch of a tree that has fallen or been cut off. “she tripped over a fallen log”

- Liquor – is an alcoholic drink produced by distillation of grains, fruits, vegetables, or sugar, that have already gone through alcoholic fermentation. Other terms for liquor include: spirit, distilled beverage, spirituous liquor or hard liquor.

- scrawny – ADJECTIVE – Word forms: ˈscrawnier or ˈscrawniest – 1. very thin; skinny and bony 2. stunted or scrubby

- lake sediments – Sediment can come from soil erosion or from the decomposition of plants and animals. Wind, water and ice help carry these particles to rivers, lakes and streams. The Environmental Protection Agency lists sediment as the most common pollutant in rivers, streams, lakes and reservoirs.

- lush palm forests – What is the meaning of lush forest? meanings of lush and forest – A lush area has a lot of green, healthy plants, grass,

- descendants – What would descendants mean? – a person who is related to you and who lives after you, such as your child or grandchild: He has no descendants. They claim to be descendants of a French duke. (countable) A descendant is something or someone that comes after something or someone (ancestor). Dogs are descendants of early wolves. You are a descendant of your grandparents. I am a descendant of Grover Cleveland.

- wrecked their own environment – What’s meaning of wrecked? – to destroy or badly damage something – verb [ T ] us. /rek/ to destroy or badly damage something: The explosion wrecked one house and shattered nearby windows.

- windblown volcanic ash – windblown – adjective – carried or driven by the wind.

- “windblown sand” – exposed to or affected by the wind. “the coastline is rugged and windblown”

- Volcanic ash – consists of fragments of rock, mineral crystals, and volcanic glass, created during volcanic eruptions and measuring less than 2 mm in diameter. The term volcanic ash is also often loosely used to refer to all explosive eruption products, including particles larger than 2 mm.

- wooden canoes for fishing – What is a wooden canoe? – A canoe is a small prehistoric wooden boat that dates back to the Stone Age. Generally narrow and pointed at both ends, canoes are human-powered boats which are propelled using single or double paddles. Canoes are light in weight and can carry one or two people at a time.

- descended – past tense: descended; past participle: descended 1. move or fall downwards. “the aircraft began to descend”

- cannibalism – What is the true meaning of cannibalism? – cannibalism, also called anthropophagy, eating of human flesh by humans. The term is derived from the Spanish name (Caríbales, or Caníbales) for the Carib, a West Indies tribe well known for its practice of cannibalism. – noun – the practice of eating the flesh of one’s own species. – “the film is quite disturbing at points with references to cannibalism”

- flesh – the soft substance consisting of muscle and fat that is found between the skin and bones of a human or an animal. “she grabbed Anna’s arm, her fingers sinking into the flesh”

- chieftains– chieftain definition: 1. the leader of a tribe 2. the leader of a tribe 3. the leader of a tribe (= a group of families).

- wooden sledges – an object used for travelling over snow and ice with long, narrow strips of wood or metal under it instead of wheels.

- hauled over log rails – haul – verb – past tense: hauled; past participle: hauled – 1. (of a person) pull or drag with effort or force. “he hauled his bike out of the shed” 2. (of a vehicle) pull (an attached trailer or carriage) behind it. “the engine hauls the overnight sleeper from London Euston”

- toppling – verb – gerund or present participle: toppling – overbalance or cause to overbalance and fall. “she toppled over when I touched her” remove (a government or person in authority) from power; overthrow. “disagreement had threatened to topple the government”

- Archaeologists – noun – plural noun: archaeologists – a person who studies human history and prehistory through the excavation of sites and the analysis of artefacts and other physical remains. “Chinese archaeologists uncovered life-sized terracotta statues”

- ‘ecological catastrophe – An environmental disaster or ecological disaster is defined as a catastrophic event regarding the natural environment that is due to human activity. This point distinguishes environmental disasters from other disturbances such as natural disasters and intentional acts of war such as nuclear bombings.

- heroic efforts – If you make an effort to do something, you try very hard to do it

- windbreaks – / something that gives protection from the wind, such as a row of trees, bushes, or a wall. Parts of buildings: fences & rails.

- contend – verb – 1. struggle to surmount (a difficulty). “she had to contend with his uncertain temper”

- walked upright. – Why does upright mean? – erect or vertical, as in position or posture. raised or directed vertically or upward. adhering to rectitude; righteous, honest, or just: an upright person.

- folklore – noun – the traditional beliefs, customs, and stories of a community, passed through the generations by word of mouth.

- manoeuvre – noun -1. a movement or series of moves requiring skill and care. “snowboarders performed daring manoeuvres on precipitous slopes”

- to roll and rock – informal : to start out or get going energetically. He was wide awake and ready to rock and roll at 5:00 A.M. Gideon Wulff.

- convinced – adjective – completely certain about something. – “she was not entirely convinced of the soundness of his motives” firm in one’s belief with regard to a particular cause or issue. “a convinced pacifist”

- tiny grooves – What does in a groove mean? – Performing very well, excellent. Performing very well, excellent; also, in fashion, up-to-date. For example, The band was slowly getting in the groove, or To be in the groove this year you’ll have to get a fake fur coat. This idiom originally alluded to running accurately in a channel, or groove.

- made by the teeth of Polynesian rats – Polynesian rats are nocturnal like most rodents, and are adept climbers, often nesting in trees. In winter, when food is scarce, they commonly strip bark for consumption and satisfy themselves with plant stems.

- doomed – What is doom with example? : to make (someone or something) certain to fail, suffer, die, etc. A criminal record will doom your chances of becoming a politician.

- decimated verb – past tense: decimated; past participle: decimated 1. kill, destroy, or remove a large proportion of. “the inhabitants of the country had been decimated” 2. HISTORICAL – kill one in every ten of (a group of people, originally a mutinous Roman legion) as a punishment for the whole group. “the man who is to determine whether it be necessary to decimate a large body of mutineers”

- shrivelled – (adjective) in the sense of withered. It looked old and shrivelled. Synonyms. withered. dry.

- peaceful and ingenious – adjective – (of a person) clever, original, and inventive. “he was ingenious enough to overcome the limited budget”

- abject – adjective – 1. (of something bad) experienced or present to the maximum degree. “his letter plunged her into abject misery”

- an unlikely story : not likely : improbable. an unlikely outcome. : likely to fail : unpromising.

- Cambridge IELTS 11 Reading Test 02

Cambridge IELTS 11 Reading Test 02

READING PASSAGE 3

Neuroaesthetics

An emerging discipline called neuroaesthetics is seeking to bring scientific objectivity to the study of art, and has already given us a better understanding of many masterpieces. The blurred imagery of Impressionist paintings seems to stimulate the brain’s amygdala, for instance. Since the amygdala plays a crucial role in our feelings, that finding might explain why many people find these pieces so moving.

Could the same approach also shed light on abstract twentieth-century pieces, from Mondrian’s geometrical blocks of colour, to Pollock’s seemingly haphazard arrangements of splashed paint on canvas? Sceptics believe that people claim to like such works simply because they are famous. We certainly do have an inclination to follow the crowd. When asked to make simple perceptual decisions such as matching a shape to its rotated image, for example, people often choose a definitively wrong answer if they see others doing the same. It is easy to imagine that this mentality would have even more impact on a fuzzy concept like art appreciation, where there is no right or wrong answer.

Angelina Hawley-Dolan, of Boston College, Massachusetts, responded to this debate by asking volunteers to view pairs of paintings – either the creations of famous abstract artists or the doodles of infants, chimps and elephants. They then had to judge which they preferred. A third of the paintings were given no captions, while many were labelled incorrectly -volunteers might think they were viewing a chimp’s messy brushstrokes when they were actually seeing an acclaimed masterpiece. In each set of trials, volunteers generally preferred the work of renowned artists, even when they believed it was by an animal or a child. It seems that the viewer can sense the artist’s vision in paintings, even if they can’t explain why.

Robert Pepperell, an artist based at Cardiff University, creates ambiguous works that are neither entirely abstract nor clearly representational. In one study, Pepperell and his collaborators asked volunteers to decide how’powerful’they considered an artwork to be, and whether they saw anything familiar in the piece. The longer they took to answer these questions, the more highly they rated the piece under scrutiny, and the greater their neural activity. It would seem that the brain sees these images as puzzles, and the harder it is to decipher the meaning, the more rewarding is the moment of recognition.

And what about artists such as Mondrian, whose paintings consist exclusively of horizontal and vertical lines encasing blocks of colour? Mondrian’s works are deceptively simple, but eye-tracking studies confirm that they are meticulously composed, and that simpiy rotating a piece radically changes the way we view it. With the originals, volunteers’eyes tended to stay longer on certain places in the image, but with the altered versions they would flit across a piece more rapidly. As a result, the volunteers considered the altered versions less pleasurable when they later rated the work.

In a similar study, Oshin Vartanian of Toronto University asked volunteers to compare original paintings with ones which he had altered by moving objects around within the frame. He found that almost everyone preferred the original, whether it was a Van Gogh still life or an abstract by Miro. Vartanian also found that changing the composition of the paintings reduced activation in those brain areas linked with meaning and interpretation.

In another experiment, Alex Forsythe of the University of Liverpool analysed the visual intricacy of different pieces of art, and her results suggest that many artists use a key level of detail to please the brain. Too little and the work is boring, but too much results in a kind of ‘perceptual overload’, according to Forsythe. What’s more, appealing pieces both abstract and representational, show signs of ‘fractals’ – repeated motifs recurring in different scales, fractals are common throughout nature, for example in the shapes of mountain peaks or the branches of trees. It is possible that our visual system, which evolved in the great outdoors, finds it easier to process such patterns.

In another experiment, Alex Forsythe of the University of Liverpool analysed the visual intricacy of different pieces of art, and her results suggest that many artists use a key level of detail to please the brain. Too little and the work is boring, but too much results in a kind of ‘perceptual overload’, according to Forsythe. What’s more, appealing pieces both abstract and representational, show signs of ‘fractals’ – repeated motifs recurring in different scales, fractals are common throughout nature, for example in the shapes of mountain peaks or the branches of trees. It is possible that our visual system, which evolved in the great outdoors, finds it easier to process such patterns.

It is also intriguing that the brain appears to process movement when we see a handwritten letter, as if we are replaying the writer’s moment of creation. This has led some to wonder whether Pollock’s works feel so dynamic because the brain reconstructs the energetic actions the artist used as he painted. This may be down to our brain’s ‘mirror neurons’, which are known to mimic others’ actions. The hypothesis will need to be thoroughly tested, however. It might even be the case that we could use neuroaesthetic studies to understand the longevity of some pieces of artwork. While the fashions of the time might shape what is currently popular, works that are best adapted to our visual system may be the most likely to linger once the trends of previous generations have been forgotten.

It’s still early days for the field of neuroaesthetics – and these studies are probably only a taste of what is to come. It would, however, be foolish to reduce art appreciation to a set of scientific laws. We shouldn’t underestimate the importance of the style of a particular artist, their place in history and the artistic environment of their time. Abstract art offers both a challenge and the freedom to play with different interpretations. In some ways, it’s not so different to science, where we are constantly looking for systems and decoding meaning so that we can view and appreciate the world in a new way.

Cambridge IELTS 11 Reading Test 02

Vocabulary List for READING PASSAGE 3

- Neuroaesthetics – Neuroaesthetics, a recently coined term, is the scientific study of the neural consequences of contemplating a creative work of art, such as the involvement of the prefrontal cortex (in thinking) and limbic systems (for emotions). Neuroesthetics is a relatively recent sub-discipline of empirical aesthetics. Empirical aesthetics takes a scientific approach to the study of aesthetic perceptions of art, music, or any object that can give rise to aesthetic judgments

- objectivity – the quality or character of being objective : lack of favoritism toward one side or another : freedom from bias. Many people questioned the selection committee’s objectivity. It can be difficult for parents to maintain objectivity about their children’s accomplishments. Employees demonstrate objectivity by detaching and reflecting on their impulses and seeking the perspective of others. They can fully explain their decisions and keep an open mind about how biases can affect them.

- masterpieces – plural noun: masterpieces – a work of outstanding artistry, skill, or workmanship. “a great literary masterpiece” Leonardo’s “Last Supper” is widely regarded as a masterpiece.

- Impressionist – noun -1. a painter, writer, or composer who is an exponent of impressionism. 2. an entertainer who impersonates famous people. adjective – relating to impressionism or its exponents. “an impressionist painting”

- brain’s amygdala – amygdala, region of the brain primarily associated with emotional processes. The name amygdala is derived from the Greek word amygdale, meaning “almond,” owing to the structure’s almondlike shape. The amygdala is located in the medial temporal lobe, just anterior to (in front of) the hippocampus.

- splashed paint – Artists that create paint splatter or paint splash art use brushes and other implements to flick, throw, or drip paint onto a canvas, rather than brushing paint directly onto that surface.

- inclination – noun – 1. a person’s natural tendency or urge to act or feel in a particular way; a disposition. “John was a scientist by training and inclination”

- perceptual decisions – Perceptual decision making is the act of choosing one option or course of action from a set of alternatives on the basis of available sensory evidence. Thus, when we make such decisions, sensory information must be interpreted and translated into behaviour. What is an example of perceptual decision? Suddenly, you see from the corner of your eye a dark object moving toward you from the right. Due to the poor light and rain, it is hard to decide what this object is and where exactly it is moving. However, you will have to make a decision to know whether you should swerve, hit the brakes, or just keep driving.

- doodles– noun – plural noun: doodles – a rough drawing made absent-mindedly. – “the text was interspersed with doodles”

- chimps – noun – INFORMAL – plural noun: chimps – a chimpanzee

- brushstrokes – plural noun: brushstrokes -a mark made by a paintbrush drawn across a surface.

- representational – relating to or denoting art which aims to depict the physical appearance of things. – “the abstract and representational elements in the same picture”

- neural activity – The neural activity pattern comprised in a memory involves a network of millions of neurons extending over a wide area. Activity patterns for different memories overlap depending on which features they share.decipher – verb – convert (a text written in code, or a coded signal) into normal language. – “authorized government agencies can decipher encrypted telecommunications”meticulously – adverb – in a way that shows great attention to detail; very thoroughly.”a meticulously researched book”

- flit across – What does flit across mean? to move quickly from one place to another without stopping long. She has flitted from one country to another seeking asylum. Birds flitted across the grass. Synonyms and related words. To move somewhere quickly.

- goosebumps – noun – a state of the skin caused by cold, fear, or excitement, in which small bumps appear on the surface as the hairs become erect; goose pimples. “this place gives me goosebumps”

- shivering – adjective – shaking slightly and uncontrollably as a result of being cold, frightened, or excited. – “he bought a warm winter coat for a shivering man” – noun – the action of shaking slightly and uncontrollably as a result of being cold, frightened, or excited. “gradually his shivering slowed”

- intricacy – noun – the quality of being intricate. – “the intricacy of the procedure” – details, especially of an involved or perplexing subject. plural noun: intricacies – “the intricacies of economic policy-making”

- perceptual overload – If an individual has a problem in more than one area, then the interaction between the senses can make the problems worse in other senses. – For some individuals, lights, colors, patterns, or contrast are interpreted as stressful, causing perceptual overload. When the system is under stress, there is a biochemical change and adrenaline or other neurochemicals are released. This has a cascading effect, causing emotional, behavioral and physical symptoms, as well as anxiety, headaches, nausea, and dizziness.‘

- fractals’ – plural noun: fractals – a curve or geometrical figure, each part of which has the same statistical character as the whole. They are useful in modelling structures (such as snowflakes) in which similar patterns recur at progressively smaller scales, and in describing partly random or chaotic phenomena such as crystal growth and galaxy formation.repeated

- motifs – noun – a dominant or recurring idea in an artistic work. – “superstition is a recurring motif in the book”

- intriguing – adjective – arousing one’s curiosity or interest; fascinating. – “an intriguing story”

- ‘mirror neurons’ – A mirror neuron is a neuron that fires both when an animal acts and when the animal observes the same action performed by another.\

- mimic others’ actions – verb – imitate (someone or their actions or words), especially in order to entertain or ridicule. “she mimicked Eileen’s pedantic voice”l

- inger – verb – stay in a place longer than necessary because of a reluctance to leave. “she lingered in the yard, enjoying the warm sunshine”

- amidst – in the middle of; amid. – “amidst this criticism, at least she still has a few people in her corner”

- embrace – accept (a belief, theory, or change) willingly and enthusiastically. “besides traditional methods, artists are embracing new technology”

- embed- verb -past tense: imbedded; past participle: imbedded 1.- fix (an object) firmly and deeply in a surrounding mass. “he had an operation to remove a nail embedded in his chest”

- Cambridge IELTS 11 Reading Test 02

Read More from IELTS Archive

- How does Paraphrasing Enhance Your Copywriting Skills?

- How Paraphrasing is Useful in Academic Writing?

- Cambridge IELTS 11 listening test 1 Answers and Audioscripts

- Cambridge IELTS 11 Reading Test 01 Vocabulary List

- Cambridge IELTS 11 Reading Test 02

Cambridge IELTS 11 Reading Test 02

just you mimics from the google translate.